The tricky bit of sublimity, Edmund Burke acknowledged in 1757, is the balance between profusion and disorder: we feel awe at the night sky because “the stars lie in such apparent confusion as makes it impossible on ordinary occasions to reckon them. This gives them the advantage of a sort of infinity.” But to artists who would seek to imitate this effect, Burke issued a caution: “unless you can produce an appearance of infinity by your disorder, you will have disorder only.” The works of art that succeed at this game “owe their sublimity to a richness and profusion of images, in which the mind is so dazzled as to make it impossible to attend to the exact coherence and agreement of the allusions.”

The sublime, in Burke’s sense of aesthetic experience entangled with peril, has often been invoked in relation to the careening, elegant mayhem of Julie Mehretu’s art. The superfluity of images that tumble across her prints and paintings succeed in defying “exact coherence,” even while suggesting elusive relationships of vast design. But where earlier painters found the requisite menace and majesty in storms at sea and vertiginous mountainscapes (J.M.W. Turner is the poster boy here), Mehretu’s topography is geopolitical. She has described herself as a “child of a failed revolution” (her Ethiopian-American family relocated to Michigan as the post-Selassie nation devolved into a bloody quagmire), and the opposing forces that drive her abstractions—energy and entropy, construction and destruction—have been soldiers in every campaign ever waged for utopia.

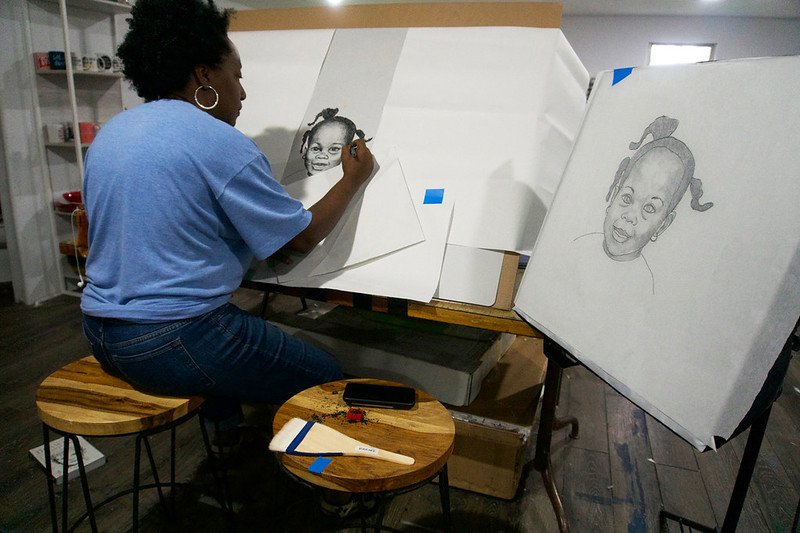

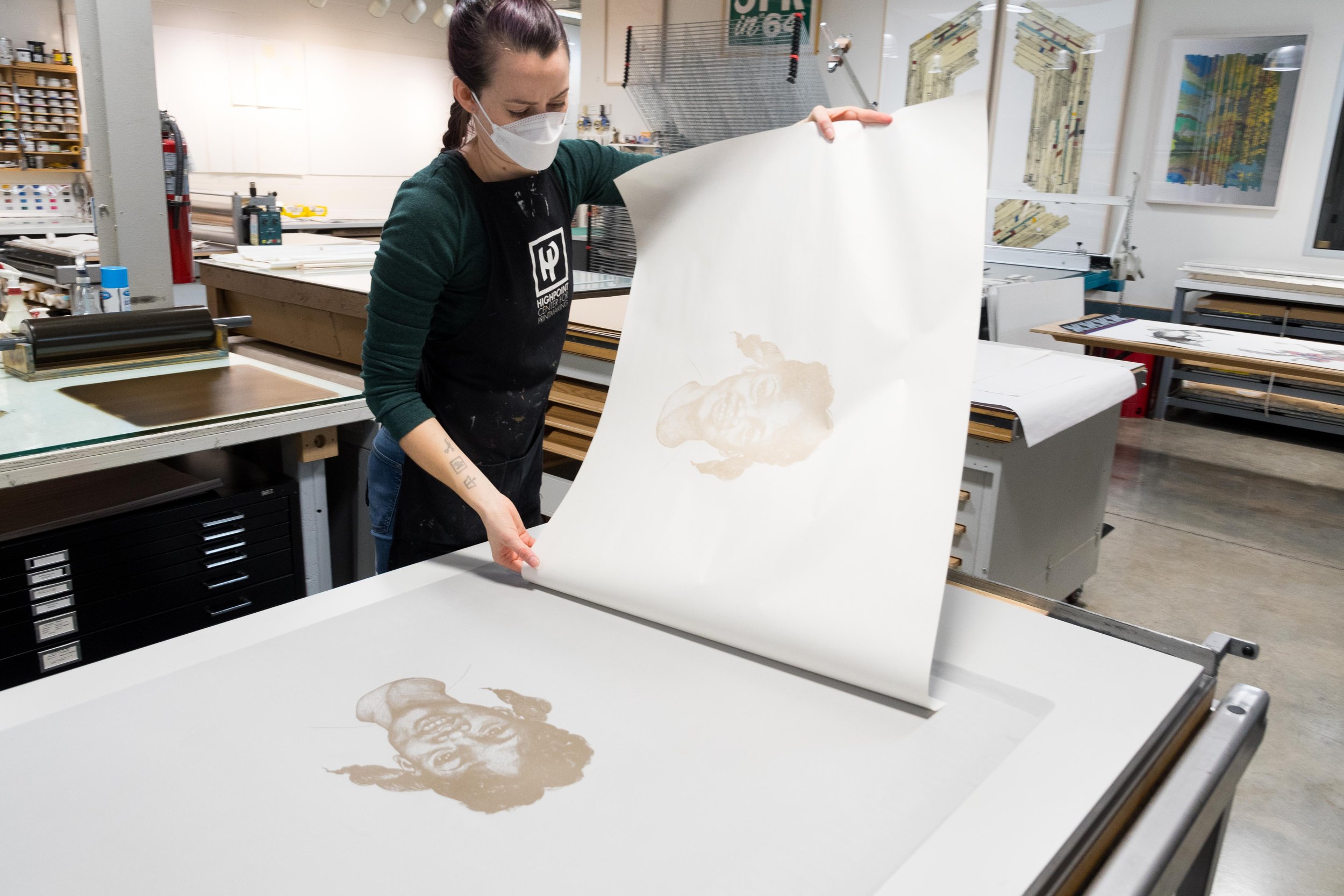

Mehretu’s infinity unfolds in layers, each rooted in a different way of thinking about the world and a different way of drawing it. Her marks may be fuzzy or lapidary, may swoop like a raptor or stammer like scuffs on a drum head, their relationships chafe as well as bind. As a graduate student she thought of her gathered lines as “social agents.” Even in painting her working habits—drawing, separation, layering, relocation—are endemic to printmaking, and it is not surprising that she has proved to be a prolific and virtuosic printmaker, collaborating with eminent print workshops on both sides of the Atlantic, almost always in etching. 1 Her projects with Highpoint are the exception. 2

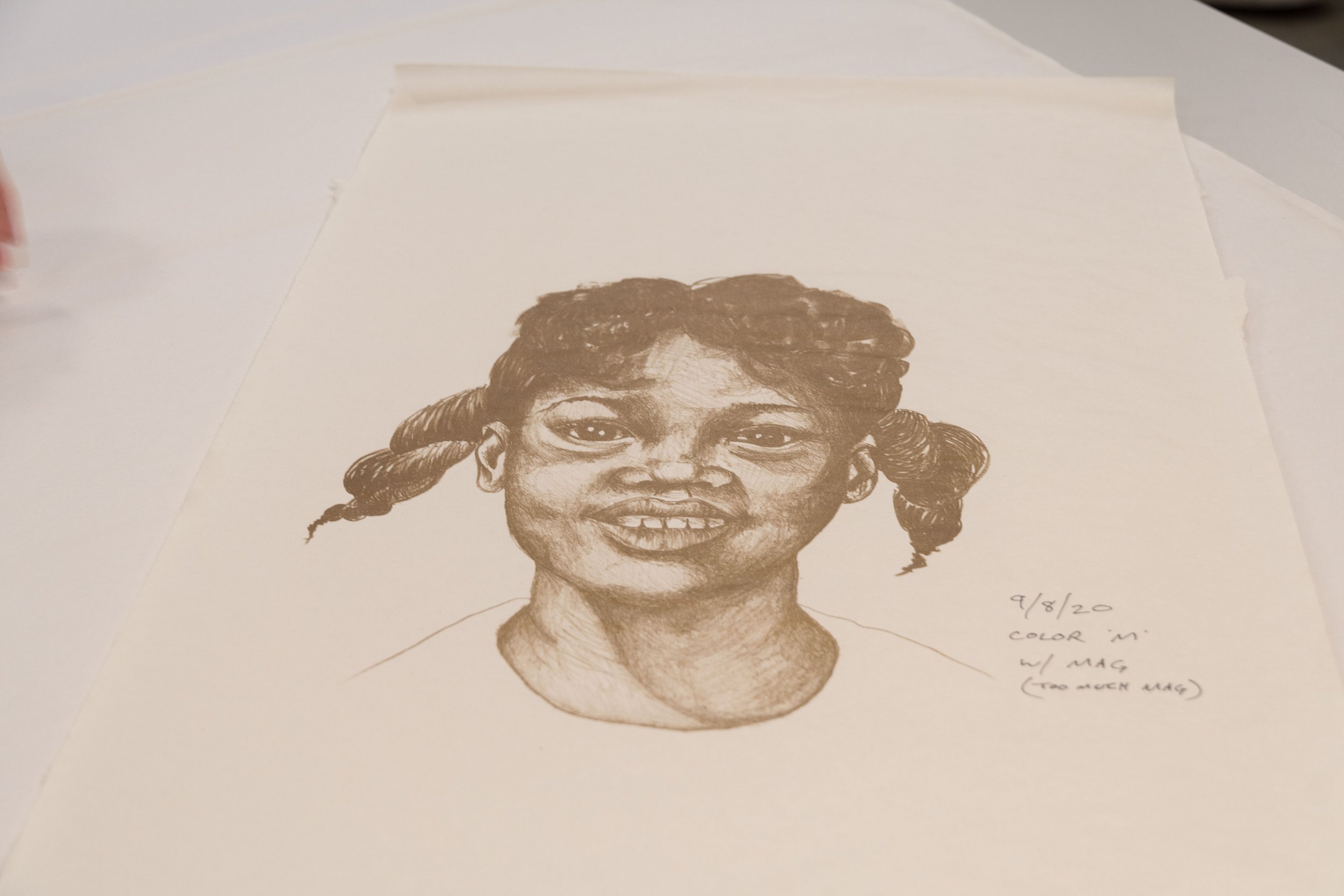

In her new prints and two earlier ones from 2003-4, Mehretu stepped away from etching’s airs and graces in favor of screenprint and lithography, once-commercial methods whose virtues include deadpan flatness and an aura of real-world plausibility. Her very first print with Highpoint, Entropia (review), features twenty-eight colors of screenprinted ink splashing east and west like the parting of a psychedelic Red Sea. Line drawings in long arcs, staccato bursts and curling filaments float in and around the spray, along with modernist architectural renderings agleam with the blithe promise of a better future. The print, like all her work, is the product of staged accretion. It began with a sixteen-layer drawing in Photoshop from which sixteen printing screens were made. She then made four further drawings on translucent mylar for lithographic plates to capture greater tonal nuance and detail. To reach the final composition, further colors were added during proofing, including translucent white layers to provide an atmospheric perspective akin to the clear acrylic layers in her related paintings).

In the meantime, however, Highpoint master printer Cole Rogers had been smitten with the appearance of Mehretu’s translucent black-and-white drawings stacked on their own. He suggested printing each of the litho plates on a separate sheet of Gampi (a thin Japanese paper), and mounting them one over the other. Pleased with the result, Mehretu tweaked the composition by adding a fourth lithographic plate. In both prints, the viewer is suspended in ambiguous space, but in Entropia (Construction), this disorientation is augmented by an eerie sense of sagittal depth, of things at a distance seen through not-quite-transparent air.

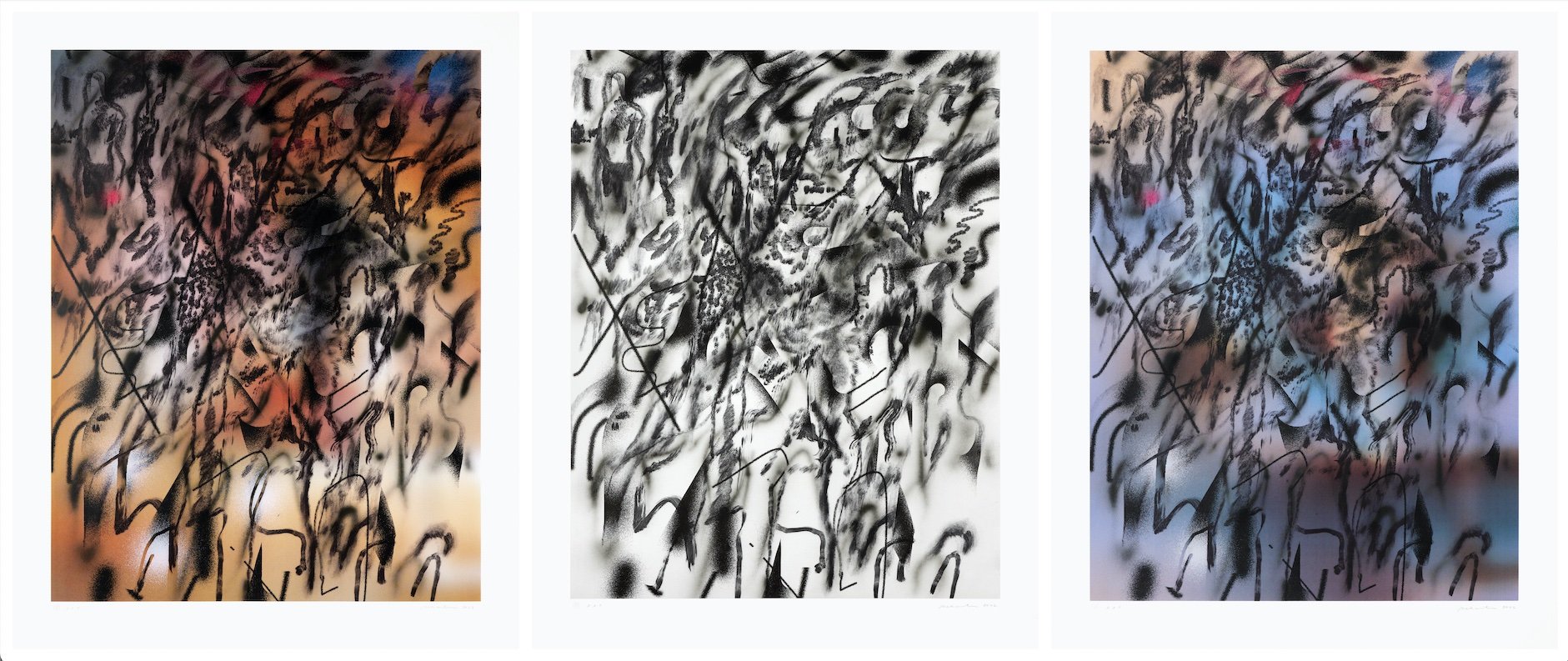

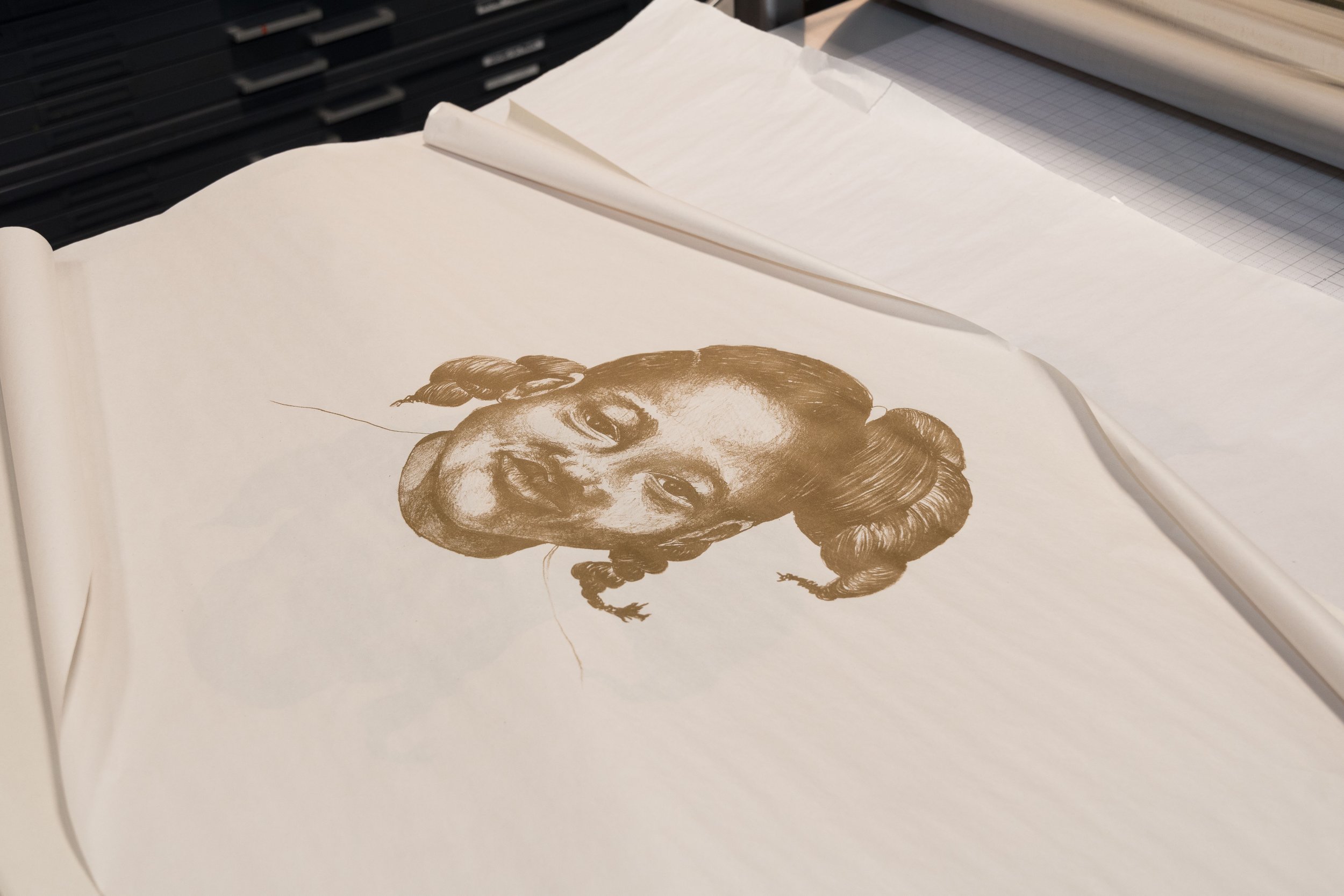

Seventeen years later, the arrival of Mehretu’s mid-career retrospective at the Walker Art Center provided an opportunity to revisit screenprint and lithography with Highpoint. She had since moved away from the kind of architectonic line drawing that underpinned the Entropia prints; photographs shot at points of jeopardy: border crossings, political protests, wildfires. Reduced to pulsing clouds of color, the action is impossible to identify in terms of location or protagonists, but even (or perhaps especially) in this state, Mehretu saw curious echoes of European grand manner history painting—a kind of formal structure and moral swagger that can be traced from Gericault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1818-19) to Joe Rosenthal’s Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima (1945) and beyond. Her hand-drawn overlays had also changed, growing looser and more expressive, and now swept like dark squalls across the new bokeh backdrops.

The new project began with a photograph of a striding protester carrying an inverted American flag and backlit by a liquor store in flames, a scene captured by AP photographer Julio Cortez four days after the murder of George Floyd and two miles due east of Highpoint, on the corner of Lake Street and Minnehaha in Minneapolis. The event was real, but were it a painting, it would have owed much to Eugène Delacroix’s exemplar of heroic hokum, Liberty Leading the People (1830), with its barefoot and bare-breasted (why?), heroine marching over a pile of corpses, the tricolor held aloft in her right hand, a bayonet in her left, while saber-rattling Frenchmen take up the rear amid martial smoke.3 The Minneapolis protester carries a bottle rather than a bayonet, but the flag, the fire, and the phoenix-like equation of destruction with rebirth attest to a continuum of political hope and rage.

Mehretu cropped the photograph, then flipped it upside down and blurred it. Though in etching she had used photo-blurs of almost diaphanous refinement, in screenprint she aimed for a coarser print terrain. In most industrial printing, all the colors of the rainbow are approximated through dots in four colors: cyan, magenta, yellow and black (or “key,” giving the process its acronym “CMYK”). The dots wax and wane in size in accordance with the colors they aim to replicate, but are regularly spaced in four interlocking grids. If the grids are fine enough, the trick works seamlessly: a speck of blue sits next to a speck of magenta, and the viewer thinks “violet.” When the resolution is less refined, weirder things happen.

Oversized “Ben Day” dots were a trope of Pop art, a tool that turned the workings of mass media into subject matter, but while Mehretu’s enlarged dot screen can be seen as a nod to photojournalism, she was less interested in the dots per se than in the visual pitter-patter of those grids as a battleground for drawing. The soft blurs now calcified into jittery rosettes of spots. Omitting the “key” black component produced a porous structure with a kind of visual tooth, while the edgy snap of screenprint means that each component reads as a discreet entity (every dot is an island, entire of itself). Over this she drew three layers of addenda, each for a different screen, each screen printed in a different black (yellow-black, purple-black, and flat black). Finally, small bursts of color were peppered on top, like flickering halations.

The dot-screen colors of Corner of Lake and Minnehaha (co-published with the Walker Art Center) reflects the incendiary palette of the original photograph (and of Minneapolis in June 2020). Her drawing layers, smoky and diffuse, operate less as strata than as currents, flowing through one another and backwards and forward in space. Each was executed with different drawing technique: one with wispy airbrush strokes; another with swift feathered marks in the manner of sumi-e brushwork; the last as a computer “dither” drawing, with spray-paint-like splotches and the kind of clean-edged wormholes familiar to anyone who has ever played with the eraser tool in Photoshop.

In the digital world, “dither” denotes the application of stochastic interference to disrupt unwanted patterns that arise when continuous information is quantized. The crude color chunks that show up in low-contrast digital images, for example, can be broken up with a spray of random dots; in sound recording, inaudible amounts of white noise can obliterate the phantom tones produced when slightly different data points are rounded to the same value. Dither, somewhat poetically, is noise as a means to quiet. Mehretu’s dither drawing is not there to fix an error but—like the jangly checkerboard of CMY dots and the quixotic fall of ink from bristles—to defy and subvert the temptations of a single coherent storyline.

In the wider world, “dither” means something else—an indulgent indecision or cozy species of panic. In both senses, it is a cousin to Burke’s dazzle: an agent of confusion endowed with strange aesthetic powers and possible wisdom. The perception of phantom patterns within complex events, after all, is the defining feature of conspiracy theories. And a mind “so dazzled as to make it impossible to attend to the exact coherence and agreement of the allusions” is a mind able to accept complexity without resorting to fables.

Burke wrote his treatise on the sublime as a young man, but for most of his life he was a politician, and his long career in Parliament encompassed both the American Revolution (he was sympathetic to the colonists) and the French (he admired the spirit and was appalled by the execution). Mehretu, the child of a more recent, failed revolution, has made herself a poet of the social sublime—the dithering, dazzling spectacle of humanity’s infinitely hopeful, endlessly myopic designs for the world. “The compositional and structural issues in my work are directly tied to the desire to take up arms and lead revolution,” she told Phong Bui around the time she began working on these prints. “But my effort is to question these gestures, to take these myths apart.”4

— Susan Tallman

Susan Tallman is a writer, critic and art historian living in Massachusetts and Berlin. She has written extensively on contemporary art, the history of prints, and other aspects of art and culture. A regular contributor to New York Review of Books among other publications, she has authored and co-authored many books, most recently No Plan At All: How the Danish Printshop of Niels Borch Jensen Redefined Artists Prints for the Contemporary World. In 2011 she co-founded the journal Art in Print, and served as its Editor-in-Chief until its closure in 2019.

Educated at Wesleyan and Columbia Universities, she is Adjunct Associate Professor of Art History, Theory and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and sits on the Editorial Board of Print Quarterly. (And, yes, she was a founding member of the New York guitar band Band of Susans.)

For inquiries about Julie Mehretu’s prints, please contact the Gallery Director: sara@highpointprintmaking.org.